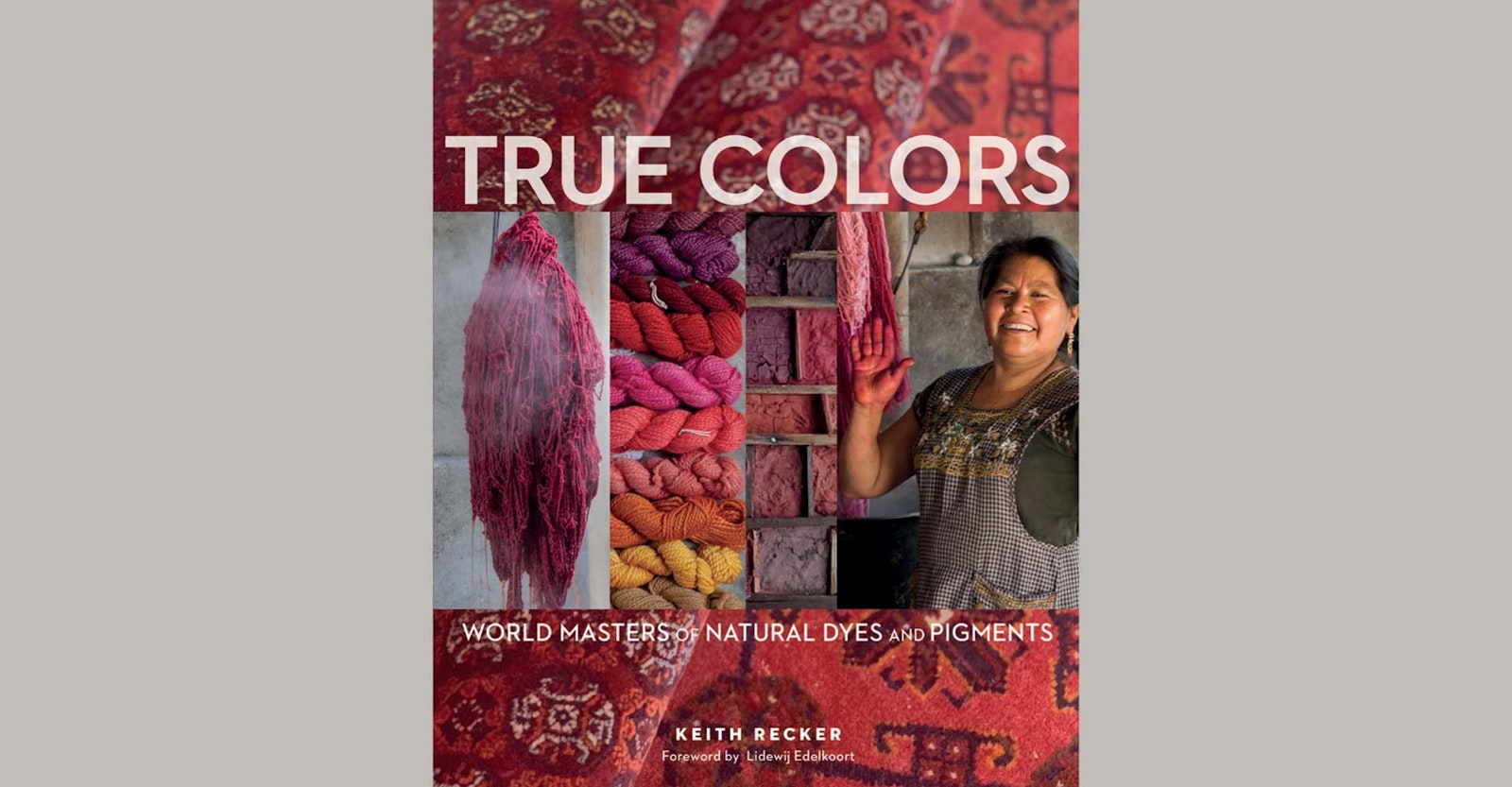

Humans have carefully extracted colors from the natural world for thousands of years. Although some of this knowledge was lost with the advent of mass-produced chemical dyes, fortunately for all of us, dyers around the world have preserved many of these ancient techniques and are developing innovative ways of harnessing natural dyes. In his new book True Colors: World Masters of Natural Dyes (Thrums Books 2019), author Keith Recker interviews twenty-eight artisans about their methods and their relationships to dyes. The following is an excerpt from the chapter “A Color of History and Faith” that features natural-dye artisan Juana Gutiérrez Contreras of Oaxaca, Mexico, an expert in dyeing with cochineal.

Juana’s favorite color is the deep, deep burgundy she coaxes out of vats of cochineal, an amazing dye source that can also produce soft pinks, vivid pinks, various reds and oranges, and a deeply satisfying rainbow of burgundies and purples.

The dye itself is carminic acid, which comes from the bodies of the female Dactylopius coccus, a parasitic scale insect that feeds on Opuntia cacti (nopales in Spanish). Carminic acid makes up approximately 25 percent of the body weight of the domesticated cochineal insect, about double the ratio of several species of wild cousins. Domesticated cochineal also lacks some of the woolly protective “coat” of wild strains, that is composed of lipid proteins that can interfere with dye absorption.

Left to right: Tiny young beetles slip through a sieve before biting into and feeding on cactus. Beetles are removed by hand, one at a time. Paddles of nopal cactus thick with cochineal beetles at bottom and fresh paddles newly infested on the top.

Juana, like most Zapotec dyers and weavers, sees cochineal as integral to the cultural patrimony of Oaxaca. Archaeologists date Oaxacan textile fragments dyed with cochineal to approximately 1000 CE, and very detailed descriptions of cochineal farming and dyeing survive from codices and missives dating to the early Spanish Colonial era. The Spanish, who eventually exported cochineal to Europe in great quantities, considered this vivid, beautiful red dyestuff “one of the great treasures of the New World,” along with gold and silver. Much has been written about cochineal’s lucrative and prestigious role in the European textile trade across the centuries prior to the invention of synthetic dyes. But the origins of the cochineal insect and cochineal dye practice are not exactly a matter around which there is universal agreement.

Some posit Peru as cochineal’s point of origin. The Peruvian textile record of cochineal stretches back 400 to 600 years earlier than Mexico’s, with subsequent increased use among the Inca, where red was a symbol of kingship. Observers point out that Mexico’s more humid conditions generally destroy ancient textiles and call into question conclusions reached only by citing Peru’s well-preserved textile remains; just because evidence does not survive in Mexico doesn’t mean it didn’t happen there first.

Left to right: Grinding dried beetles on a stone metate. Weighing cochineal on its way to the vat.

Recent mitochondrial DNA studies of domesticated Dactylopius populations in Mexico, Peru, and Madeira (the latter population introduced from Mexico) show more genetic diversity in Mexico, a strong indication that the species originated there. Others refer to Mexico’s greater diversity of predators feeding on cochineal as a sign that “Mexican cochineal and its predators have been coevolving for a much longer time than their Peruvian equivalents.”

By way of explaining the ancient domestication of cochineal, Juana and her family refer to the domestication of corn. “People in this area took a simple grass and turned it into our most important food, so they knew something about breeding,” she says, clearly not much interested in discussing Mexican versus Peruvian cochineal. She’s more engrossed in the colors she makes with it. “I feel the colors I get from cochineal, especially dark burgundy, because I relate it to my faith. Long ago in church I saw the red blood of Jesus, and cochineal brings me back to the fact that He died for us. It’s emotional. It’s powerful. It’s alive,” she says. “I feel its magic.”

Juana and Antonio produce a few kilos of cochineal themselves—less than a fifth of what they use each year—mainly to show visitors to the workshop the full story of cochineal dyeing. There are always several dozen paddle-shaped leaves of nopal hanging in their courtyard, protected from rain, heat, and birds that might eat the beetles. Every three months in warm weather and every four months in cold weather, each mature beetle is brushed by hand from the cactus into a bowl with a tiny flat stick. Smaller beetles are left on the cactus for another week or two to grow. When the insects are harvested, the nopal is composted to make room in the courtyard for new cactus leaves.

Left to right: Juana Gutiérrez Contreras first dyes yarn yellow with pericón and then overdyes with cochineal to achieve a rich red. This rich aubergine color, yarn is first dyed yellow with pericón, then overdyed with cochineal, and finished in an iron-rich bath of pomegranate skins.

Bowlfuls of harvested beetles are tossed into a sieve, which is tapped gently over fresh nopal leaves laid flat on the floor of the courtyard. Tiny young beetles pass through the sieve and onto their new homes. It only takes a few hours for the beetles to bite into the nopal and begin feeding. Once the little ones choose a place to feed, they don’t budge, and the nopal leaves are hung undisturbed until the next harvest time comes around.

The harvested beetles are dried and then ground on a stone metate prior to a dyeing session. The luscious purple-red powder is first dissolved and then filtered through cloth as it enters the dye vat, eventually producing an equally luscious range of pinks, reds, oranges, and purples, depending on what is added to the vat or how the yarn is treated beforehand.

When Juana mordants yarn with lengua de vaca leaves, she can create pink cochineal shades that darken to dusty violet in an iron vat, or fully saturated purples when overdyed with indigo. Mordanting with alum pushes cochineal toward the reds. An iron vat will darken these tones toward burgundy. She achieves still other colors by using yarn already dyed with pericón that, when overdyed with cochineal, turns coral, orange, or warm red. The most delicious, rich aubergine emerges when these warm reds are immersed in a vat of pomegranate.

To read more about Juana and other dyers around the world, look for True Colors by Keith Recker online at www.thrumsbooks.com or at your favorite book store.

Photos by Joe Coca