A true Wisconsinite, Mary Burns set up her studio in northern Wisconsin in her grandparents’ house, a 15-minute drive from Lac du Flambeau Reservation and 100 miles north of Wausau, where she grew up. The soft-spoken, poised artist draws her energy and inspiration from the outdoor world and feels blessed to be surrounded by the woods and lakes she’s known since childhood. The large weaving studio she built to nurture her creativity is a safe haven where she can reflect on cultural or environmental issues she eventually incorporates into her designs.

The studio conveys a sense of respect for excellent craftsmanship and reveals the weaver’s mindful approach to her art. Weavings inspired by the beauty of nature or the designs of Frank Lloyd Wright are on display for local art tours. Handcrafted tapestry beaters, felt work, and countless wooden shuttles, pirns, and small frame looms carefully stored in birchwood baskets give visitors a glimpse of the artist’s multiple talents.

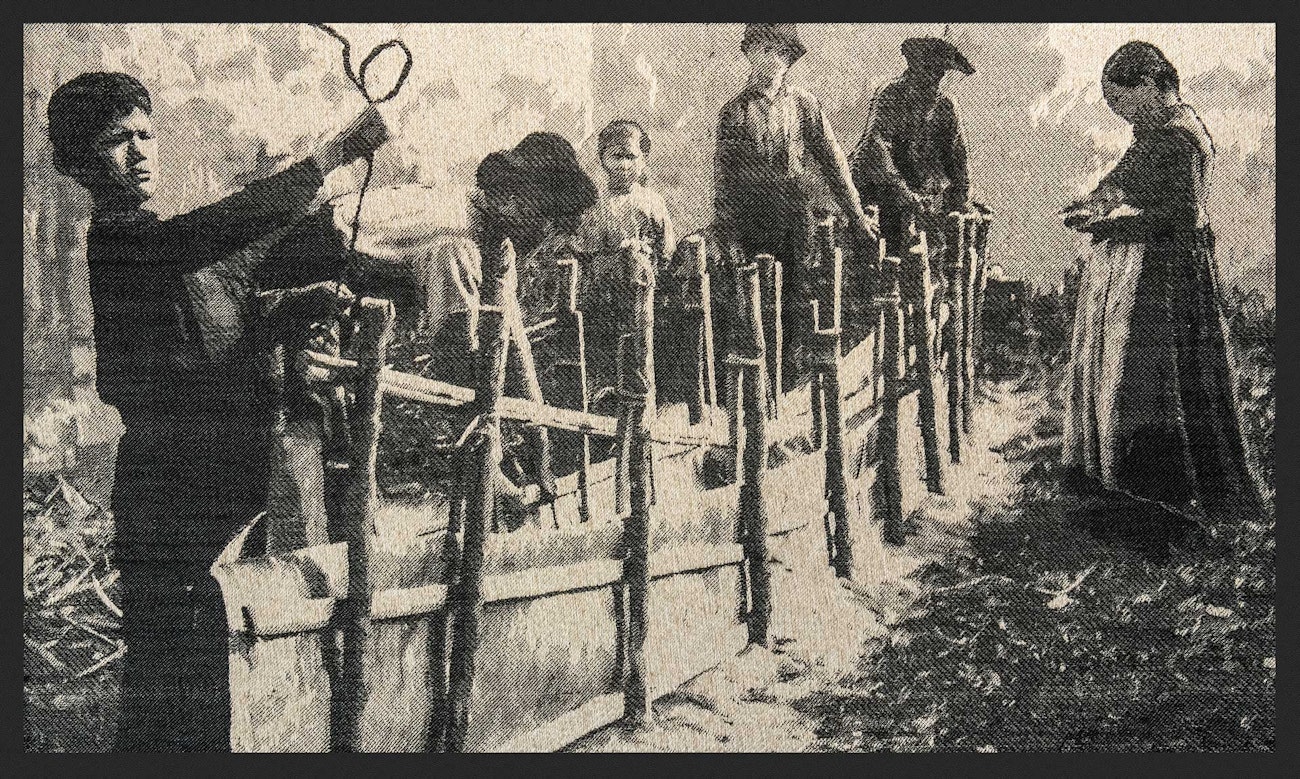

From the Ancestral Women exhibit: Birch-bark Canoe Building, 50" × 31". This Jacquard weaving by Mary Burns is based on an original photograph by Truman Ward Ingersoll from the late 1890s.

A weaver, writer, and teacher, Mary Burns found her vocation in her high school art class when basic tapestry weaving instantly resonated with her. In college, Mary learned how to use a floor loom with multiple harnesses, eventually buying a sturdy old Scandinavian-style floor loom with a bench built into the framework. She fixed it up and used it for some years until she bought a brand-new 5-foot Glimåkra loom that was, as she recalls, heavenly compared to weaving on her rough barn loom. The major turning point in her career came when she took a class from Peter Collingwood, the innovative master weaver who developed the shaft-switching technique.

“The shaft-switching system gives you more design freedom,” says Mary. “You have these levers on the top of your loom, and it allows you to move a warp thread from the first harness to the fourth harness. So in effect, it’s giving you more weaving-design options. This workshop really helped me to make the leap into shaft switching, and I wove most of my wool rugs on my 8-foot-wide Cranbrook loom with the shaft-switcher system. The rugs are heavyweight, combining New Zealand rug wool weft with linen warp.”

The pursuit of creative freedom took Mary to the Montréal Centre for Contemporary Textiles, where she attended several workshops taught by prominent Jacquard weaver Louise Lemieux Bérubé. Jacquard weaving has been the true object of her affection ever since. “In tapestry weaving you are manipulating the warp threads by hand. It’s a discontinuous weft, which means the weft shuttle does not go from edge to edge, from selvedge to selvedge. It actually builds up colorways in specific areas. In Jacquard weaving, you are weaving selvedge to selvedge. My TC2 Jacquard loom has 1,320 warp threads, and I can individually control every single one. This loom was developed in the 1990s by Norwegian weaving professor Vibeke Vestby. She made Jacquard weaving available to studio weavers; it was a big step for me.”

“Technically, I wind the warp onto the warp beam on the back of the loom, and those threads are individually pulled up and threaded through the heddles and then through the reed in a specific pattern. I’m currently using 16/2-weight warp threads, threaded at 45 ends per inch. It will take me two weeks to thread the loom because I break it up to rest my eyes.”

Jacquard weaving by Mary Burns of Diana Miller with her grandmother, Che-Mon Louise Amour, Menominee Indian Tribe of Wisconsin, 33" x 42", Ancestral Women exhibit.

The Ancestral Women Exhibit

The Ancestral Women exhibit, in which she portrays elder women and clan symbols of Wisconsin First Nations, is Mary’s strongest woven statement yet. The project was created to honor elder women of the 12 native tribes of Wisconsin. Woven from private photographs, the portraits shed light on the women and the clan symbols or sacred places that are meaningful to each woman. As soon as she began researching this project, all roads led to Mildred “Tinker” Schuman, “Eagle Woman,” in Lac du Flambeau.

“When I asked who would be a good representative, everyone said Tinker Schuman! I did a lot of meditating to find the right way to do this exhibit. The spiritual content of this project was on my mind from the start; I wanted to be respectful and honor these women and their cultures. Tinker invited my husband and me to do a pipe ceremony and pray with her. These were spiritual and emotional moments. It’s an honor to participate in that. I hope that my work conveys that spiritual essence.

For her portrait, Tinker as “Eagle Woman” from the Eagle Clan of Lac du Flambeau, Wisconsin, wore regalia she made after receiving powerful dreams. For her deer-toe dress, she traded beadwork for deer toes with a man from Lac du Flambeau who needed baby moccasins for his grandchild.

The eagle staff standing next to her in the portrait has 13 eagle feathers. They represent the 13 moons, the 13 months, and women. The small feathers represent the four races of people, Black, Red, Yellow, White, all symbolizing life. They also symbolize the four directions. The words Ogichi Daa kwe wa mean “Warrior Woman.” Tinker takes her eagle staff to Moon Dances and Water Walks.

“Most of the elders in the portraits are passed on now,” Mary says. “These women were the backbone of their communities. They really kept the families together and their traditions alive. This project is about them. I feel like I am a vessel for bringing this project to the public. I worked with the tribes to develop the weavings, and a number of women were so thankful to see their ancestors being honored. This is telling me that it was time these women had that recognition.”

For the First Nation life scenes that were part of the same exhibit, Mary worked from actual photos primarily with the Minnesota Historical Society and the Wisconsin Historical Society. For the piece titled Birch-bark Canoe Building, she redrew the background because there wasn’t enough distinction between the people building the canoe and the background on the original photos. Mary recalls, “I did a very small version of that piece some years ago and had it on display in the studio. During one of the art tours, a man who kept looking at this small piece said to me, ‘I think that my grandfather took the original photo this weaving is based on.’ I knew this photograph had been taken by a professional photographer named Truman Ward Ingersoll from St. Paul, Minnesota. He really was this man’s grandfather. It was very incredible! He lives in Duluth and just happened to be coming on the art tour and stopped at my studio!” This life scene series was done using the same technique as in the portraits: black thread for the warp, and one tan color thread with an off-white thread wound together to create a sepia tone, for the weft.

The long creative process started with the tribes providing old photographs of the women they wanted to be honored in the exhibit. Then Mary worked with the families or the communities, collecting as many details as possible to develop a design that would incorporate all the aspects of that person.

Mary Burns Describes the Artistic Process

“Tinker ‘Eagle Woman’ asked to be featured with an eagle and her eagle staff. I drew the eagle and took some photos of her eagle staff. Then I worked from photos of her. For the background, I sketched out Strawberry Island, a sacred place in Lac du Flambeau, and took some photos, too. Tinker is the only Pipe Carrier in the exhibit, so we decided she should have her pipe in the weaving; I took more photos of her just holding her beautiful red pipe bowl.

“Tinker’s portrait combines the work I had done from the photos and the work I’d done drawing out the background. I put this preliminary material in Photoshop and worked from these layers of drawings and photos to create one design. That was pretty complex, and it involved a lot of shading. Then I put all this material into Pointcarre, my Jacquard weaving program, and simplified the designs, bringing them to a point where I could weave them. I worked to reduce the colors and shades to bring it down to 12 to 14 shades. I simplify the design while trying to retain the essence of what I’m trying to portray.

“The whole design process took me weeks on each of the portraits. For each of the shades, I would assign a weaving structure to create all the shading. The lightest value would bring out more of the weft color, which is generally a sepia tone, and the darkest value would bring out the black from the warp. Then I would fill in from the lightest to the darkest value by adding a little bit more of the black warp for every step as you get darker.

“For the weft, I used two threads that I wound on pirns for the shuttles. One is generally a natural off-white, a 10/2 weight, and the other shade is a sepia tone, a 20/2-weight cotton thread. Sometimes I would use a little different tone in that beige and brown color range. Some have a more yellowy-gold tone to them. These Jacquard pieces are all cotton. On other weavings, I occasionally put in a little wool or a little glittery yarn, but they are mostly all cotton. For my full-color pieces, I generally put up to four different colored threads on the shuttle to create a certain color or a hue that I am looking for.”

The Women + Water Exhibit

The upcoming Women + Water exhibit continues Mary’s strong narrative with portraits of water activists. The first pieces portray Native American women working to raise public awareness about water issues and how water needs to be protected. This exhibit will include activists, scientists, and limnologists (water scientists) from around the world. The first completed piece was a portrait of water activist Josephine Mandamin from Wikwemikong First Nation in Ontario, who sadly passed away on February 22, 2019, at the age of seventy-seven. “I contacted her and told her about this project and my interest in weaving her portrait as the first one in this series,” says Mary. “I was so honored that she was willing to let me weave her portrait. I wove two pieces based on a photo, and then I met with her and gave her one of them; it meant so much to me.” Autumn Peltier is the great-niece of Josephine Mandamin and the youngest water protector to be included in this project. The fourteen-year-old water activist is from Ojibwe and Odawa heritage and comes from Wikwemikong Unceded Territory in northern Ontario. She was nominated in 2018 for the International Children’s Peace Prize and recently became the new Anishinabek Nation Water Commissioner.

The next portraits for this project will be of two sisters from Lac du Flambeau who were suggested by Tinker because they are veterans and very strong women. This project is merging with an artist residency at the Trout Lake Station, which is a field station of the Center for Limnology at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Mary will create portraits for this residency and will work on natural dyeing projects with fellow artist Debra Ketchum Jircik. They will be collecting water samples and studying how natural dyes can be affected by different types of water as water chemistry and composition varies from one lake to another.

To learn more about Mary Burns and her projects, visit manitowishriverstudio.com.

Portrait of Mildred “Tinker” Schuman from the Eagle Clan, of Lac du Flambeau. She’s a poet, beader, Pipe Carrier and tribal elder.

Mildred “Tinker” Schuman, “Eagle Woman”

Tinker Schuman and Mary first met to discuss the Ancestral Women exhibit. Tinker describes the memory: “Mary and her husband, John, came to my house to show me her weavings, then we smoked the pipe. I felt honored that she asked me to be part of this project. When she asked me to write a poem, I had to pray and think about the very essence of these portraits. It all came together in the poem ‘Ancestral Women of Creative Spirit.’ It’s about our ancestral women, what they went through and endured when their children were taken away and put in boarding schools. They went through a lot of historical trauma, including alcohol and many issues that were prevalent at these times, and they didn’t have much hope.

“The assimilation effort changed our ways of life. Our spiritual life was underneath, you could not openly practice your spirituality. People were sent to Catholic, Baptist, or Protestant churches in the summer. I was brought up that way, but I knew there was something missing in my life. When I was 18 years old, it all came together when I went to the cities and met other Native American people. I realized we had our ways. I picked that all up and attended many ceremonies. I was getting all kind of dreams and visions. An elder told me to go to Pipestone, Minnesota, to get a hand-carved sacred pipe in catlinite stone. I went to South Dakota at Crow Dog’s Paradise for a Sun Dance ceremony with this sacred pipe. You need to fast for four days before a Sun Dance, and when you’re dancing, sometimes people may bring you something to drink, like chokecherry medicine. It’s all so beautiful. It’s unbelievable that I could do something like that. It’s amazing that our high spirit in our bodies can do such a thing. Today, people come to me from all over different areas, praying, looking for help, so I’m just a tool to help them.

“I learned the Ojibwe language later. My parents spoke the language, but they would not let us know because they were afraid for us, afraid of what might happen to us. There are Ojibwe speakers on the Reservation, but all our elder ones are gone. Now we have Ojibwe language classes and a podcast produced by the Lac du Flambeau Ojibwe Tribe and recorded by Leon ‘Boycee’ Valliere for beginner to intermediate students. You can learn the language when you go to ceremonies, too.”