Ellen:

One of my earliest childhood memories is of the magnificent loom that lived in my grandparents’ basement. The loom was my grandfather’s, and it was primarily used to weave rugs. However, when I envisioned my own weaving, I always imagined a fine, crisp yardage that would be sewn into something. It would be decades until my dream was realized.

In mid-February 2020, just before the world turned upside down, I received a 15-inch rigid-heddle loom. At that point, my days were busy: I had classes to teach, patterns to write, and projects to knit. I promised myself I’d get serious about learning to weave when things slowed down. And then in March 2020, slow down they did. A lot. Being self-employed, I was used to working mainly from home and fortunate that much of my daily routine stayed the same. However, I became acutely aware of how much of my creative energy was fueled by spending a couple of hours each week knitting with friends.

I was stressed and tired. I couldn’t focus on work and could hardly knit a stitch. Yet somehow, I could weave dish towels—lots and lots of dish towels. By midsummer, as I was getting good with my little loom, a second loom entered my life in the form of a Baby Wolf from a friend who was downsizing her studio.

On this new-to-me loom, I wove more towels, some scarves from a kit, and overshot-trimmed dinner napkins (my first sewable yardage). Even though I wasn’t feeling comfortable with much else in the world, by early 2021, I was feeling comfortable with weaving. I could turn away from the doom and gloom when I sat in front of my loom.

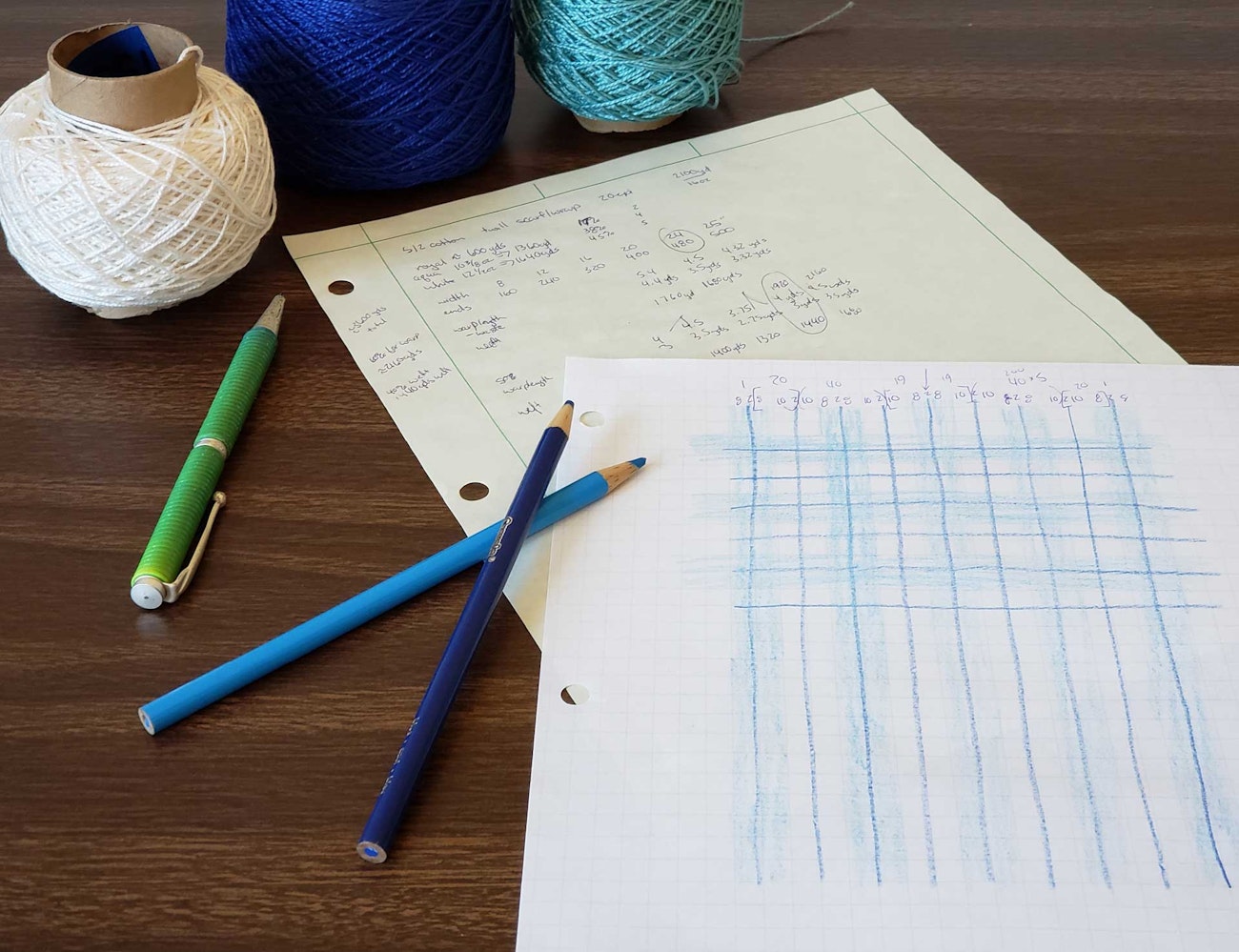

To keep my mind occupied, I decided to weave fabric suitable for sewing. I chose three partial cones of 5/2 cotton from my stash and worked backwards through the usual planning process to determine how much fabric I could create with those yarns as opposed to figuring out how much yarn I would need to create a certain amount of fabric. My goal was to maximize the total fabric woven and minimize waste.

I chose an appropriate twill sett and guessed my picks per inch. I estimated the yardage on each cone, did some back-of-the-envelope calculations to come up with the warp and weft usage, and sketched out plaid variations with the proper ratios of each color. The yarn hit the loom, and I wove an attractive length of fabric.

Then, I realized that one important step was missed in my planning. I hadn’t thought about what I was going to sew. The fabric was ready to be sewn into something, but it wouldn’t tell me what it should become.

I reflected and realized that many people had a hand in this fabric’s creation—from the family that indirectly passed down a heritage of weaving, to the fiber friends who provided me with looms, yarn, and, most importantly, encouragement (not to mention the many skilled hands that were involved in the creation of my yarn and tools). Perhaps this fabric needed to be placed into another set of hands to reach its full potential.

Because I still was not able to meet with my real-life fiber friends, I went virtual and offered the fabric for sale or trade in my weekly knitting newsletter (The Chilly Dog): “Look what came off the loom! After wet-finishing, the fabric is approximately 2.75 yards long and 20.5 inches wide made with 5/2 cotton, so it’s pretty thick and squishy. If this one-of-a-kind length of handwoven fabric was meant to be yours, I am entertaining offers (including trades).”

One subscriber responded. The fabric was carefully wrapped with a few surprise goodies from my stash and journeyed north to Christine Livingston in Alaska.

A sketch and some quick calculations led to fabric, fashion, and friendship. Photo by Ellen Thomas.

Christine:

When I first saw the plaid fabric in The Chilly Dog newsletter, I cooed—I may have even drooled a bit. Amidst a global pandemic, and reeling from a recent attempt at downsizing, I felt so textile deprived that I was ready to enjoy weaving, if only vicariously through another’s handiwork. I’ve never tired of plaid, so when I saw that Ellen was entertaining offers for trade, I immediately replied. She proposed that we exchange “surprise” packages. I received her box and responded in kind.

The photo in the newsletter inspired a vision of a plaid pencil skirt with a youthful kick pleat, a vintage-style lapped zipper at center back, and a Petersham waistband finish. The twill had great texture and charm; it wasn’t tightly woven but was stable just the same. My initial skirt idea was spot-on.

I have sewn with my own handwoven cloth before and therefore had a healthy respect for the medium. My first task was to find the ideal skirt pattern. I chose a classic three-piece straight skirt by Susan Khalje (see Resources). The pattern with side seams shifted to the back would be an ideal canvas for the plaid.

With plaid, pattern layout is always a huge consideration. In this case, I had no choice but to place the front pattern piece at the widest point of the yardage and line up the two back pieces accordingly. In the end, I had to sacrifice skirt length to match the plaid.

Sewists know that once you cut into handwoven cloth, you are racing against the clock. While the generous 2-inch seam allowances provided some insurance against fraying, the pearl cotton lacked the barbed nature of wool, and I was concerned that the fragile cut edges would not stand up to the manipulation needed to match the design of the fabric at the seams and darts. Although a fusible stabilizer would have secured those pesky edges, it would also have affected the drape and character of the cloth. Therefore, although I stabilized the waistband, zipper, back slit, and hem, I refrained from underlining the entire skirt. For peace of mind, I zigzagged along the seam allowance edges before cutting into the fabric, but I resisted the urge to serge until the main seams were constructed for fear of distorting them.

The most critical aspect of this project was lining up the twill pattern at the darts and seams. I felt the alignment of the plaid would make or break the skirt. The inherent imperfections of handwoven cloth make lining up a plaid pattern on the first go unlikely. To avoid ripping out seams, I found it beneficial to pin baste, hand baste, and machine baste before completing the final pass with a machine stitch.

I can’t imagine lining a handwoven garment with anything less than a high-quality cotton or silk. I was fortunate to find a medium-weight silk douppioni of just the right color in my stash. Once inserted, the lining gave sufficient structure to the skirt without affecting drape.

Inevitably, I needed to make concessions during the construction process. Fearing that a lapped zipper would be too bulky, I inserted an invisible zipper instead. And while I loved the romantic notion of a Petersham ribbon treatment, the skirt looked a little naked without a waistband. Using some of the leftover fabric cut on the bias, I constructed a simple folded bound waistband. The bias cut added interest to the skirt and “dressed” it nicely. At this point, I was intimately acquainted with my fabric and doubted that the center-back seam would support the weight of a kick pleat, so I opted for a simple slit. The construction required lots of handsewing, but I like to think that handwoven cloth deserves it.

The skirt is a keeper. It is a classic style of demi-couture construction with the emphasis on Ellen’s beautiful fabric.

Note the beautifully matched plaids! Photo by Julia Vandenoever

RESOURCES

- Susan Khalje Couture. The Straight Skirt. susankhalje.com.

AUTHORS

CHRISTINE CARRELL LIVINGSTON of Anchorage, Alaska, is a retired music teacher with a love of textiles. An avid spinner, weaver, and sewist, she is rarely without knitting needles in her hands.

ELLEN THOMAS from The Chilly Dog is a knitting designer, technical editor, and teacher living in Decatur, Alabama. Her patterns and tutorials are available at thechillydog.com or peek at her works in progress @thechillydog on Instagram.