For years I listened to the Big Bopper’s song “Chantilly Lace” without wondering what, exactly, Chantilly lace was. In fact, as a child I sang it all as one word as “shantillyace” in the way kids are wont to do when they don’t understand the actual lyric. Later, I remember asking my mom, who thought it was a type of cake (she wasn’t entirely wrong; there is a such thing as both Chantilly cake and Chantilly cream), but now I know that what the Big Bopper actually liked was an exquisite form of bobbin lace.

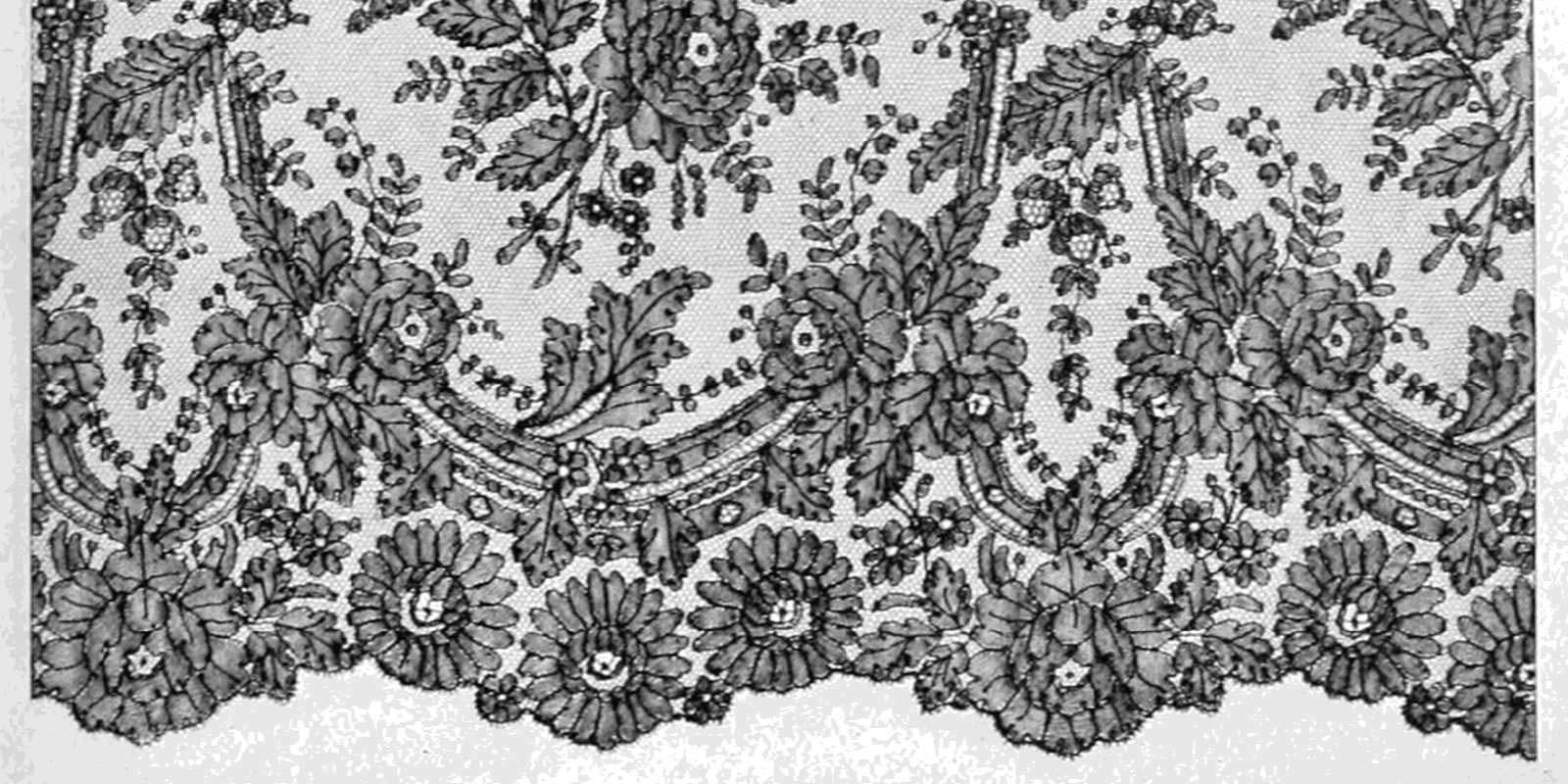

Chantilly lace originated in France in the 17th century and was named after the city of Chantilly, where it was originally produced. Often this lace features highly detailed images of flowers and plants, heavily outlined as if drawn on the fabric with an ink pen. Originally the lace was made in an off-white color known as blonde, but soon black eclipsed blonde as the most popular color, as black lace was the must-have fabric in Spain.

Chantilly gloves. Photo Credit: MoMu - Fashion Museum Antwerp. Creative Commons 3.0 license: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/deed.en

Throughout the 18th century, aristocracy in American, Spain, and France proudly wore Chantilly lace. Many famous women, including Marie Antoinette, sought it out for their wardrobes. Then came the French Revolution. Not only after Marie Antoinette was executed, so too were the lace-makers, who were seen as in league with the aristocracy. Thus ended the reign of Chantilly lace, at least until it was revived with the help of none other than Napoleon at the start of the 19th century.

For decades, Chantilly lace was once again the darling of the upper classes, although by this time manufacture had moved from Chantilly to Bayeux. It surged in popularity, reaching its height around the 1830s and then declining throughout the latter part of the century. A machine was invented that could produce Chantilly lace faster and cheaper than humans could with bobbins and, even worse, lace shawls became distinctly unfashionable. Eventually the lace houses went bankrupt and many of the paper patterns were destroyed.

Fortunately, Chantilly lace and the traditional methods of making it were not entirely lost to time, thanks to enthusiastic modern bobbin lace makers who revived old patterns, created new ones, and who teach others how they can make this timeless lace. I’m sure the Big Bopper would approve.

Happy Weaving!

Christina

PS: If you love learning about lace, make sure to check out PieceWork’s back catalogue of Lace Issues. Might I suggest starting with the May/June 2013 issue which includes the delightfully titled article “Spinsters, Free Maids, Tells, and Shakespeare.”