|  |

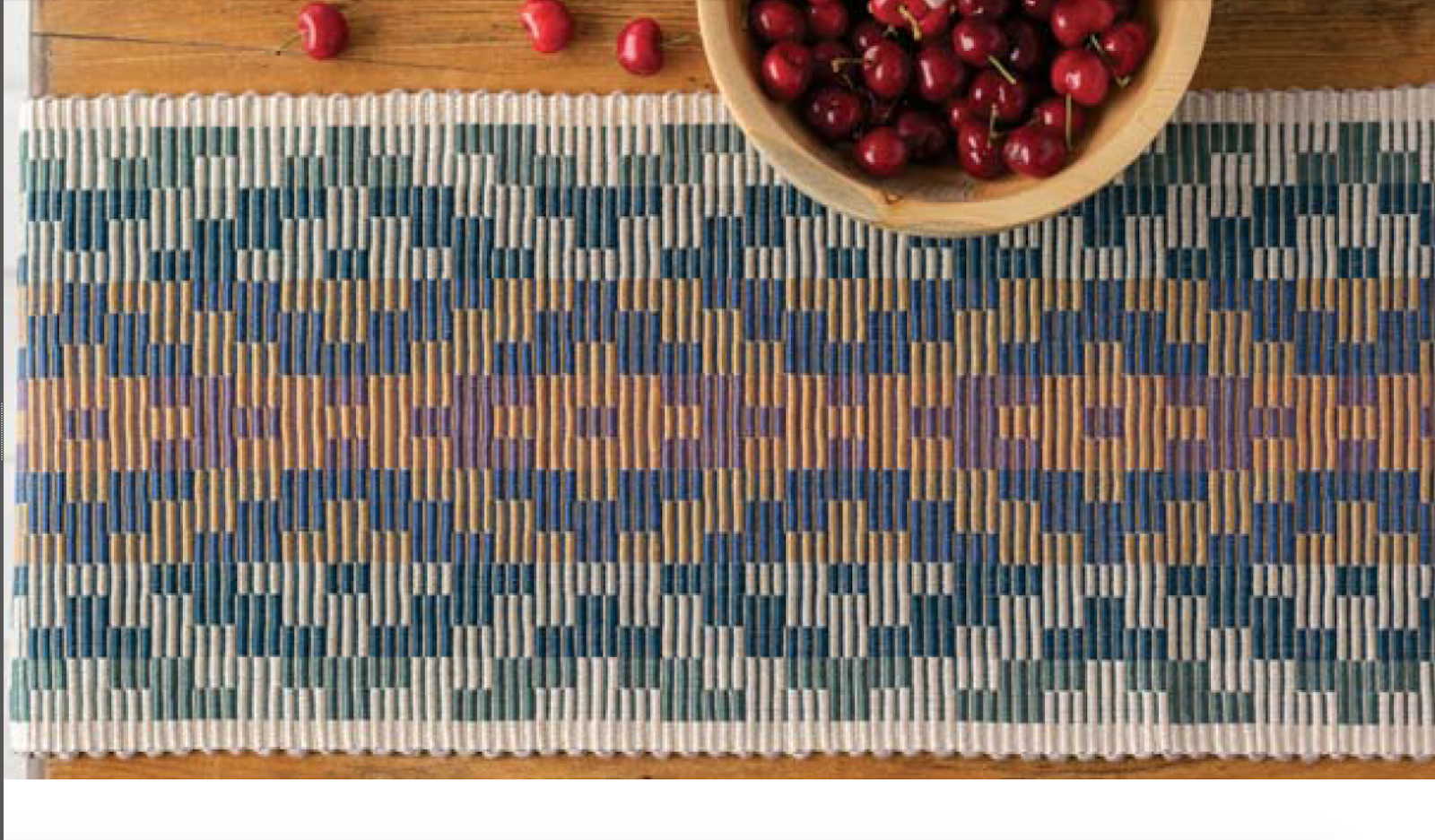

| Karen's handwoven satin awaiting its destiny as a pillow. |

Handweavers may weave for decades without ever trying one of the major weave-structure classifications. The usual progress is plain weave, then twill, then block weaves and then infinite variations on those.

So why does satin get such short shrift? Satin is the backbone of Jacquard weaving because the high warp-dominant vs weft-dominant contrast creates wonderful patterning possibilities. But for handweavers, not so much. I’ll admit I never considered weaving satin until it was required for a school assignment.

As a weave structure, satin is characterized by long weft floats on one side and long warp floats on the other, with no discernible twill line. Within any given satin unit, weft floats are tied by one warp end per pick and vice versa. The single-warp lifts are not consecutive but are a set number of shafts away from each other. This number is called the satin counter and depends on the number of total ends in the satin unit.

Satin units must have at least five ends, one on each shaft. True satin isn’t possible on six shafts because the counter cannot be spaced evenly. After that satin can have as many ends per unit as available shafts and practical float length allow. The long floats and scattering of the interlacements among successive picks is what gives satin its smooth texture, high density, and beautiful drape.

As a textile, true satin must be woven of filament yarn. A satin-structure cloth woven of staple yarn is called sateen. When satin is woven without patterning, the warp-float side is considered the right side. On a handloom, however, satin is often woven weft-floats-up because lifting one shaft is much easier than lifting all the others.

That’s the technical gist. As someone who just pulled two yards of filament satin off the loom, I can add a few practical insights.

With a straight-draw threading, one-shaft-per-treadle tie-up and one-shuttle, and straight treadling, weaving satin is fast and easy, even with the extra ends and picks needed to achieve the correct density. However, accuracy is essential. Missed picks are almost impossible to see on the weft-float surface until you spot them on the warp-float underside working their way toward the cloth beam, or more likely, as you unwind the woven cloth from the loom.

For a structure/pattern weaver like me, weaving satin gets old quick unless you have enough shafts and treadles to alternate between warp floats and weft floats for blocks or weft-wise stripes.

Materials matter. Fine filament silk makes the ultimate true satin, but that’s pricey, especially considering the density. Different staple yarns yield very different results for what is technically sateen. I found a fine filament viscose rayon in a soft burgundy and dull gold in my stash and wove an eight-end satin in a double-stitched variation G.H. Oelsner calls English leather. After wet-finishing, it became smooth and shiny on one side and textured on the other with a drape resembling . . . well, a Slinky.

- What does one do with a length of satin that, while smooth and drapey, feels a little creepy on the skin? I’m thinking pillows, but satin pillows will cry out for special embellishment. Luckily, I have Jacqui Carey’s *200 Braids to Twist, Knot, Loop or Weave *in my library. There’s a beautiful twisted braid on page 134 with beads, gimp, and cotton that would make a great edging.

Will I weave satin again? Not on a regular basis, but I’m glad I added this fundamental weave structure to my design toolbox. It will come in particularly handy when I take that Jacquard class in a few years.