Subscriber Exclusive

Planning a Weaving Project: Part 2

Balance in weaving has multiple meanings. You can balance a design or a draft, and you can weave balanced weave. Susan and Melissa break it all down in this second part of the series.

Balance in weaving has multiple meanings. You can balance a design or a draft, and you can weave balanced weave. Susan and Melissa break it all down in this second part of the series. <a href="https://handwovenmagazine.com/planning-a-weaving-project-part-2/">Continue reading.</a>

https://handwovenmagazine.com/cdn-cgi/image/format=auto/https://www.datocms-assets.com/75077/1656653711-hwjf22-oak-forest-towels-graves.jpg?auto=format&w=900

Here is the second part of this series about planning weaving projects by Susan Bateman and Melissa Parsons of the Yarn Barn of Kansas. In the first part, they addressed how to get started by narrowing the options to start a plan and how to develop the outlines of a project and draft. This part of the series is about some of the many ways that balance affects a design and a draft. —Susan E. Horton

SUBSCRIBER EXCLUSIVE

Here is the second part of this series about planning weaving projects by Susan Bateman and Melissa Parsons of the Yarn Barn of Kansas. In the first part, they addressed how to get started by narrowing the options to start a plan and how to develop the outlines of a project and draft. This part of the series is about some of the many ways that balance affects a design and a draft. —Susan E. Horton

[PAYWALL]

The term balance in weaving has multiple meanings. It can refer to a design, repeat, to an entire draft, or to the weaving itself.

Balancing repeats and drafts

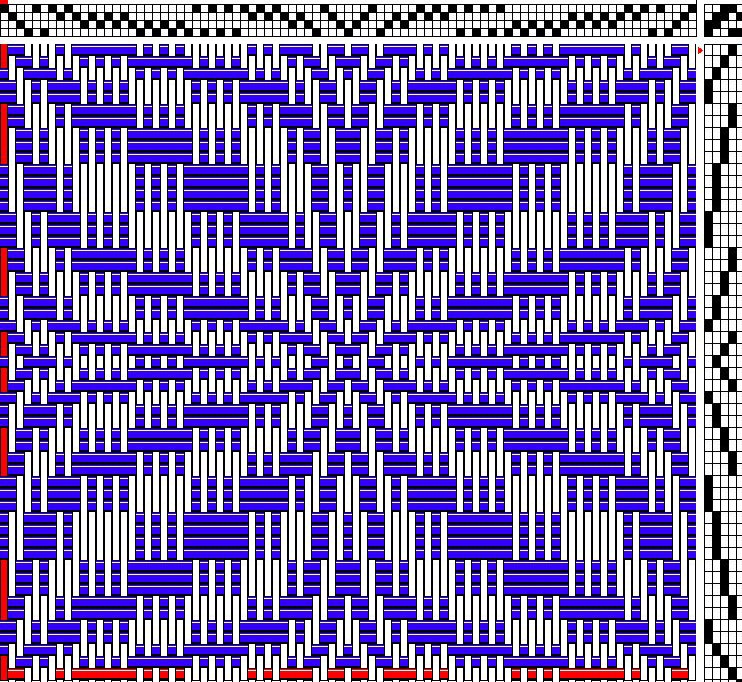

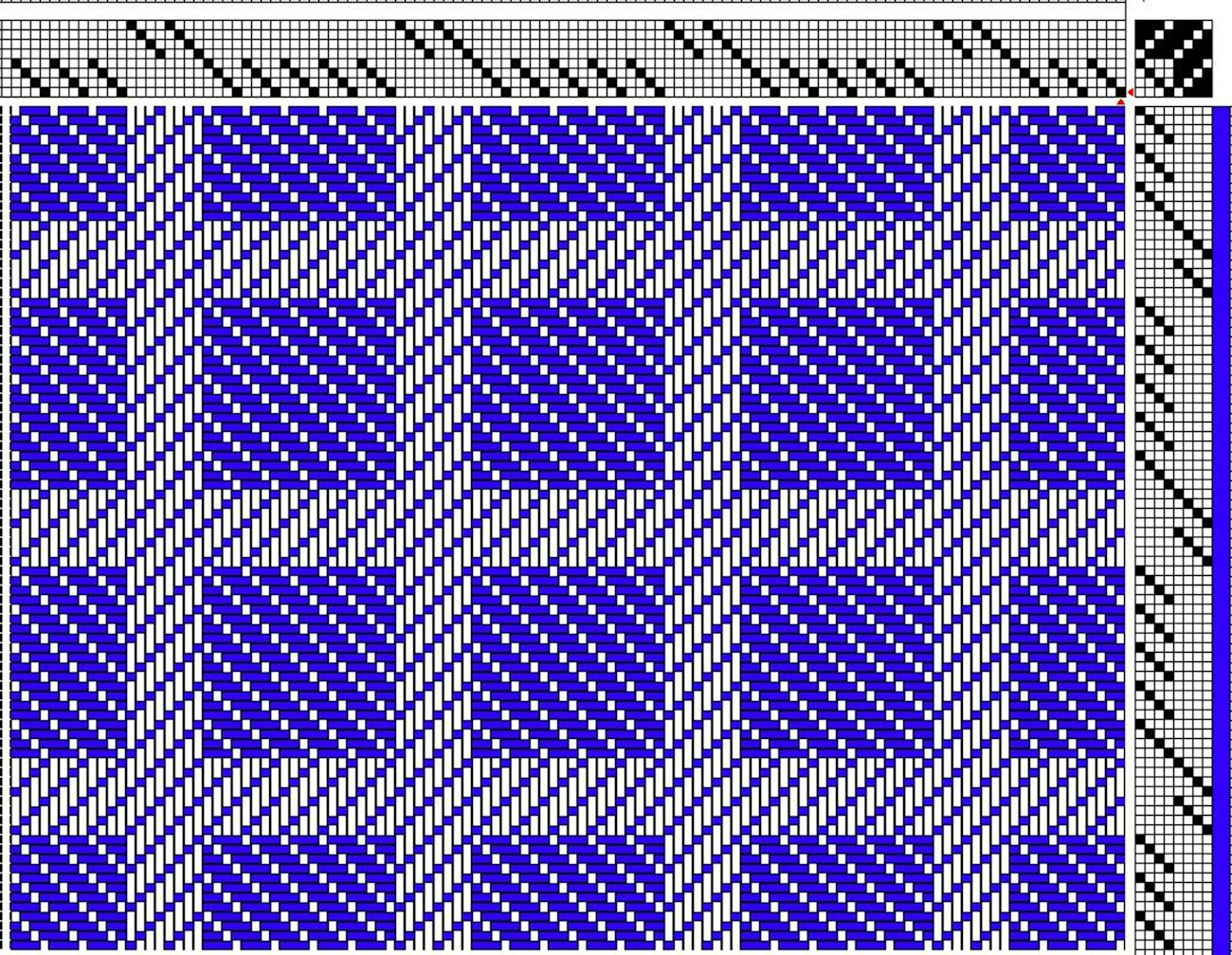

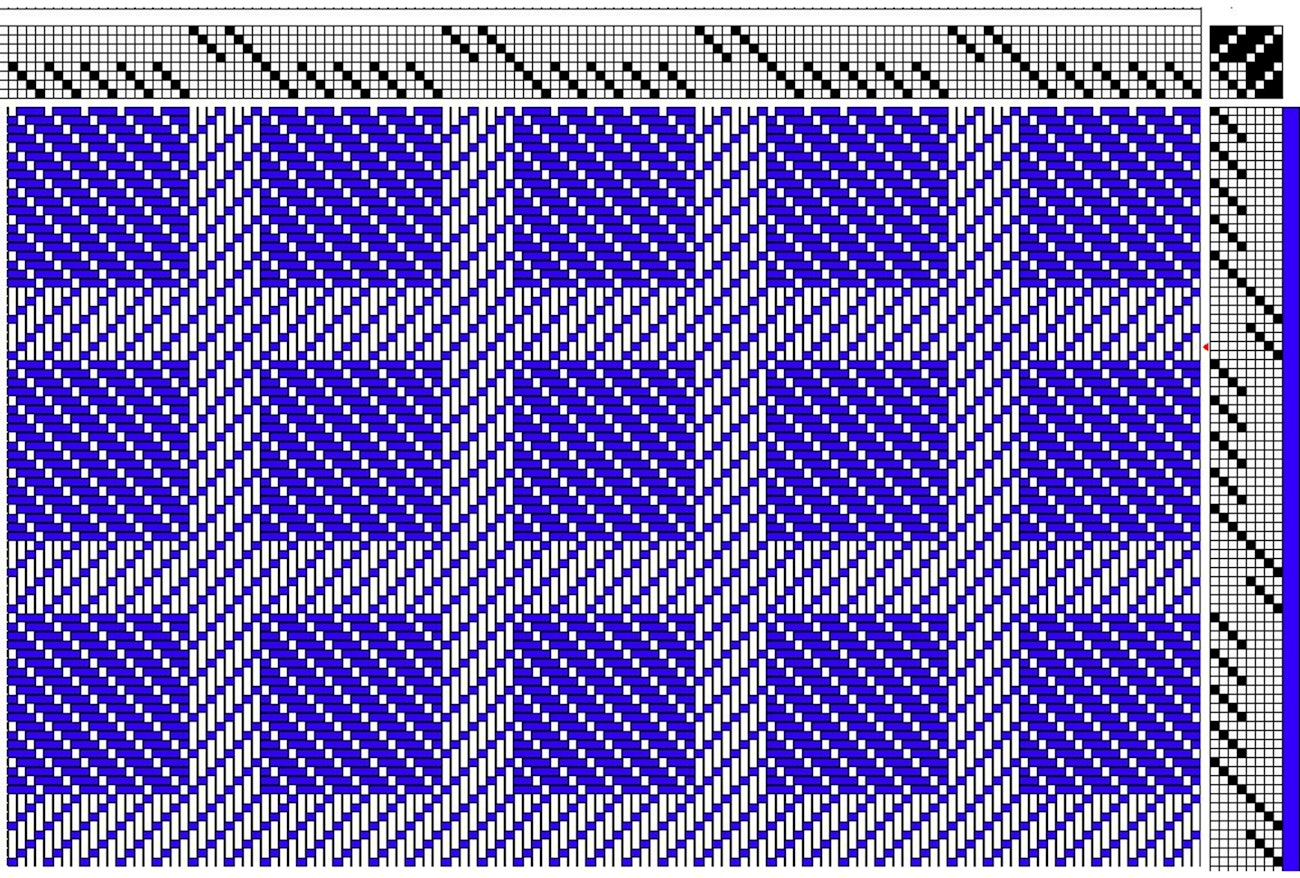

The term balance in a draft or pattern refers to a portion of a repeat that is used to make the design symmetrical and/or complete. Balances can be one warp end or weft pick, or they can be many. To start, let’s go back to the blooming leaf overshot pattern that we talked about in the first part of this series. Below is one repeat of the pattern. Notice the red warp end added to the drawdown on the left. That is a balance warp end, and the weft pick highlighted in red at the bottom is a balance weft pick.

In one repeat of a motif, add balance ends and picks (shown here in red) to complete the pattern.

If you were designing a piece with only one repeat of this motif, you would add that last warp end and that last weft pick to complete it, as we did above. However, if you were designing a piece that had multiple repeats, you would wait until the last repeat to add the balance threads and complete the pattern. If you added the balance threads to every repeat, you would end up with doubled warp ends and doubled weft picks, as shown below.

When combining repeats, don’t add the balance ends and picks (shown here in red) until you come to the last repeat in the threading and in the treadling.

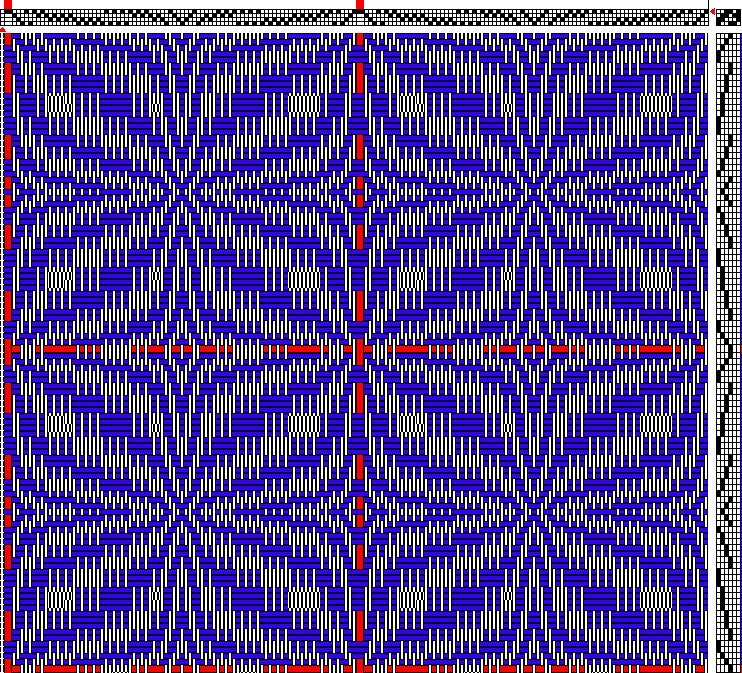

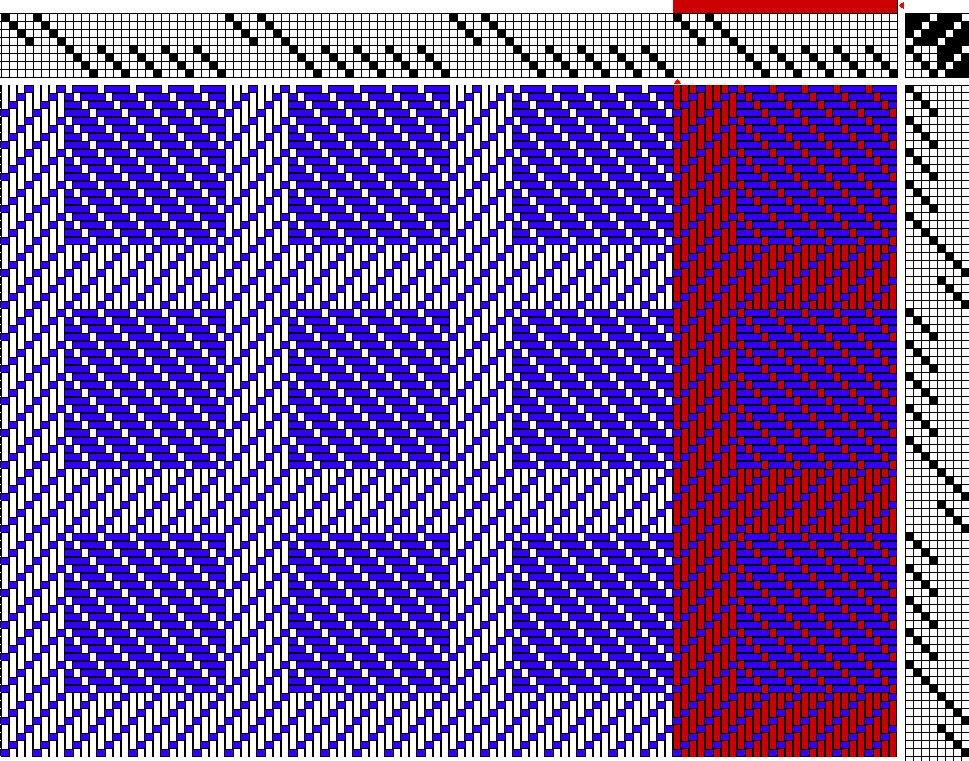

There are also times when you will want to balance an entire draft so that it is symmetrical. The idea is the same as for one warp end or weft pick balance but may require adding partial repeats or deleting partial repeats to balance a draft within a design.

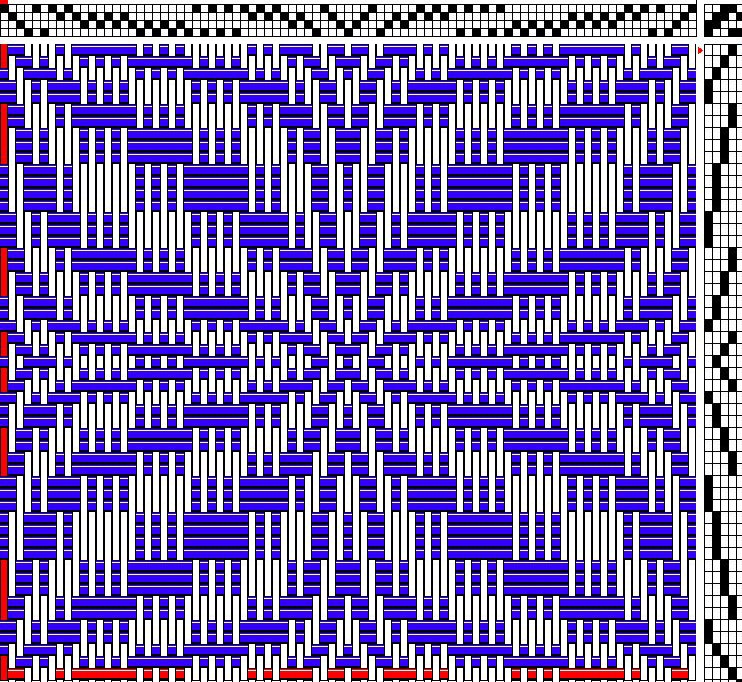

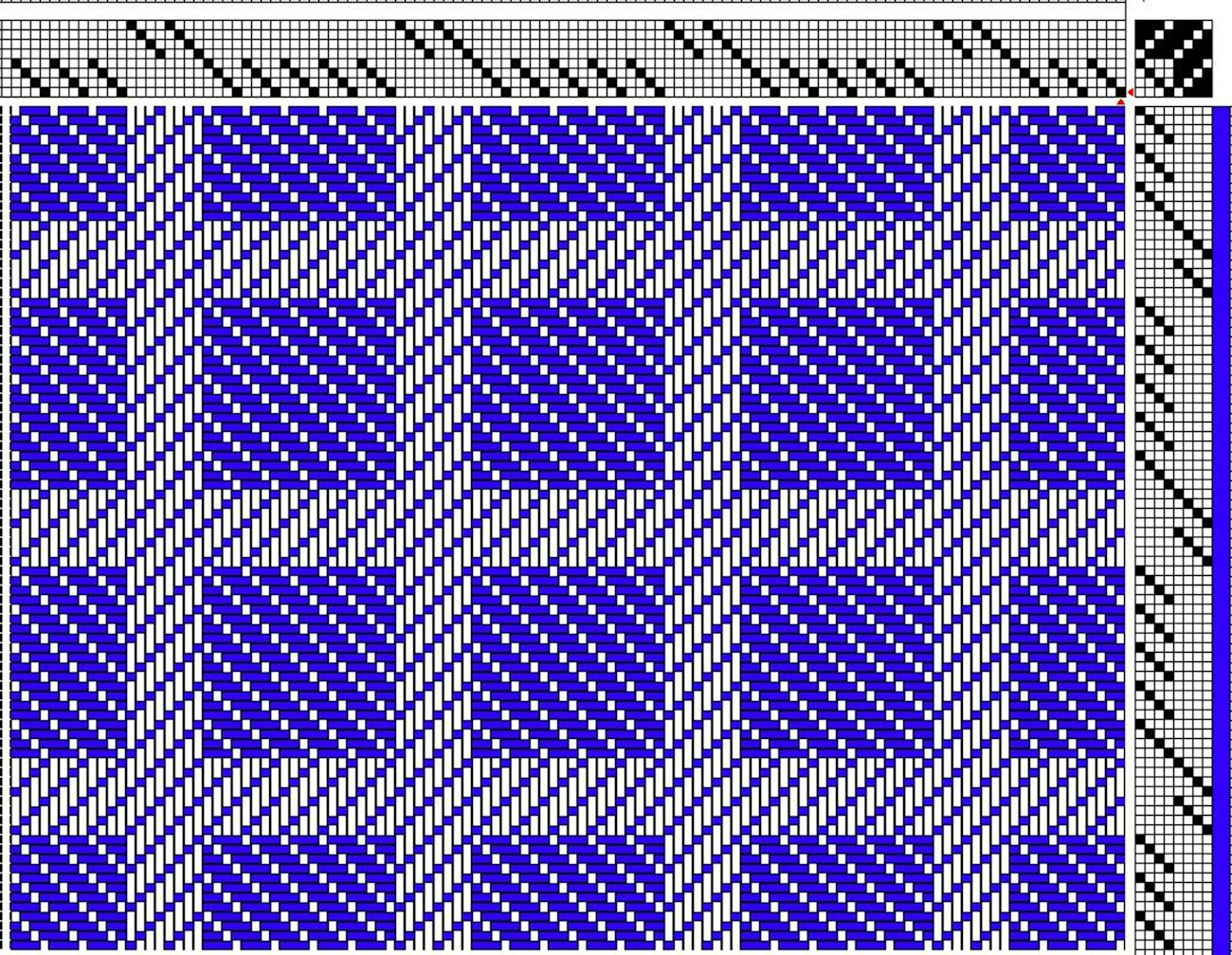

Below is a complete drawdown for a placemat, allowing you to visualize the entire piece. The shaded part is the warp repeat, and it has been repeated four times across the warp. The design is perfectly fine! But if you want it to be symmetrical with or without borders on both sides, you need to add or subtract a portion of a repeat.

Four threading repeats of this turned-twill draft create a pattern with a border on the left but no border on the right.

Look at the second version of this threading below. The first 20 ends from the right have been repeated on the left side so the design is symmetrical. Do you like the proportions and/or will there be too much or too little warp width for what you are planning? If they aren’t right for you, adjust them until they are.

In this version, the two sides are equal, and there is no outer border.

In the last version, shown below, instead of repeating 1-2-3-4 for a total of 5 times on each side, we narrowed it to just 3 times, for a trimmer look. Once you have a version of the threading you like, look at the total ends and make sure the width still works for the piece you want to weave.

Note how the edges match in this final version.

In the examples above, we have been talking about the warp, but the same is true with the weft sequence. You might decide to adjust the treadling in the same way so that your fabric is symmetrical in the treadling sequence as well.

Balanced and unbalanced weaves

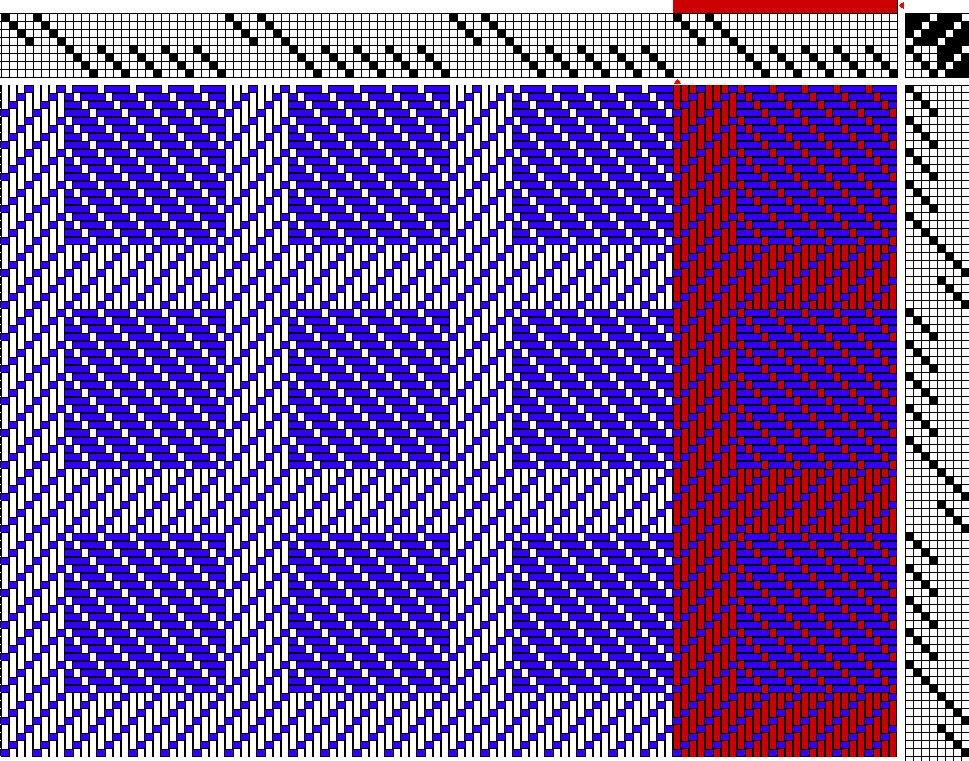

A balanced weave means that the warp and weft have the same setts (epi = ppi) and they both show equally in the finished cloth. If your warp and weft are about the same size, and your sett is correct, you can usually expect to have a balanced weave. This is what unadjusted drawdowns illustrate. A balanced weave is important if you want your weaving to look like the draft you’ve designed.

Tracy Kaestner wove a balanced twill for her Buffalo Plaid Chore Jacket from Handwoven Jan/Feb 2022. Photo by Matt Graves

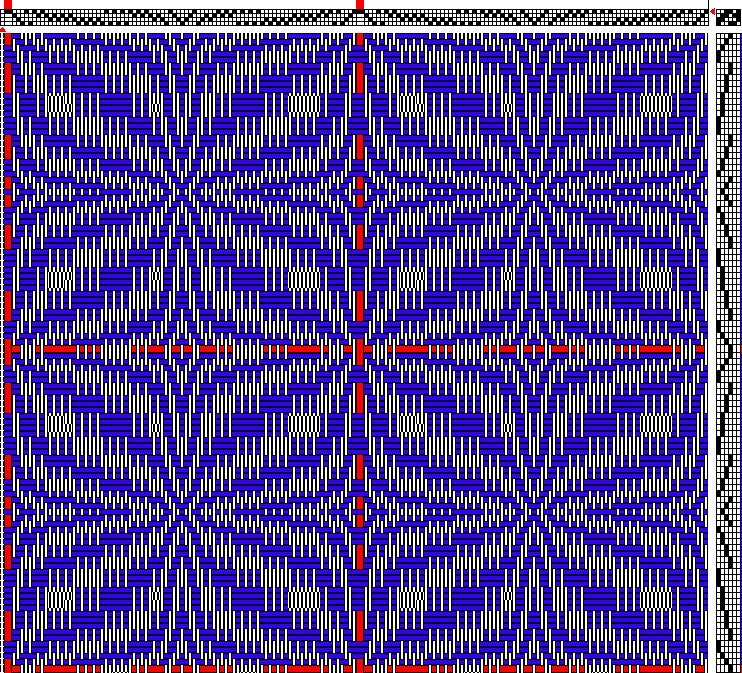

If your warp sett isn’t the one you need for a balanced weave, you may have more picks per inch, which will compress the design vertically or fewer picks per inch, which will elongate it. It’s okay if you don’t want the weave to be balanced, but you should make that decision consciously and take it into account in your calculations of number of repeats, dimensions, and yardage requirements. Sampling is the only way to know for sure whether you will or won’t have a balanced weave and whether you will be satisfied with your final results.

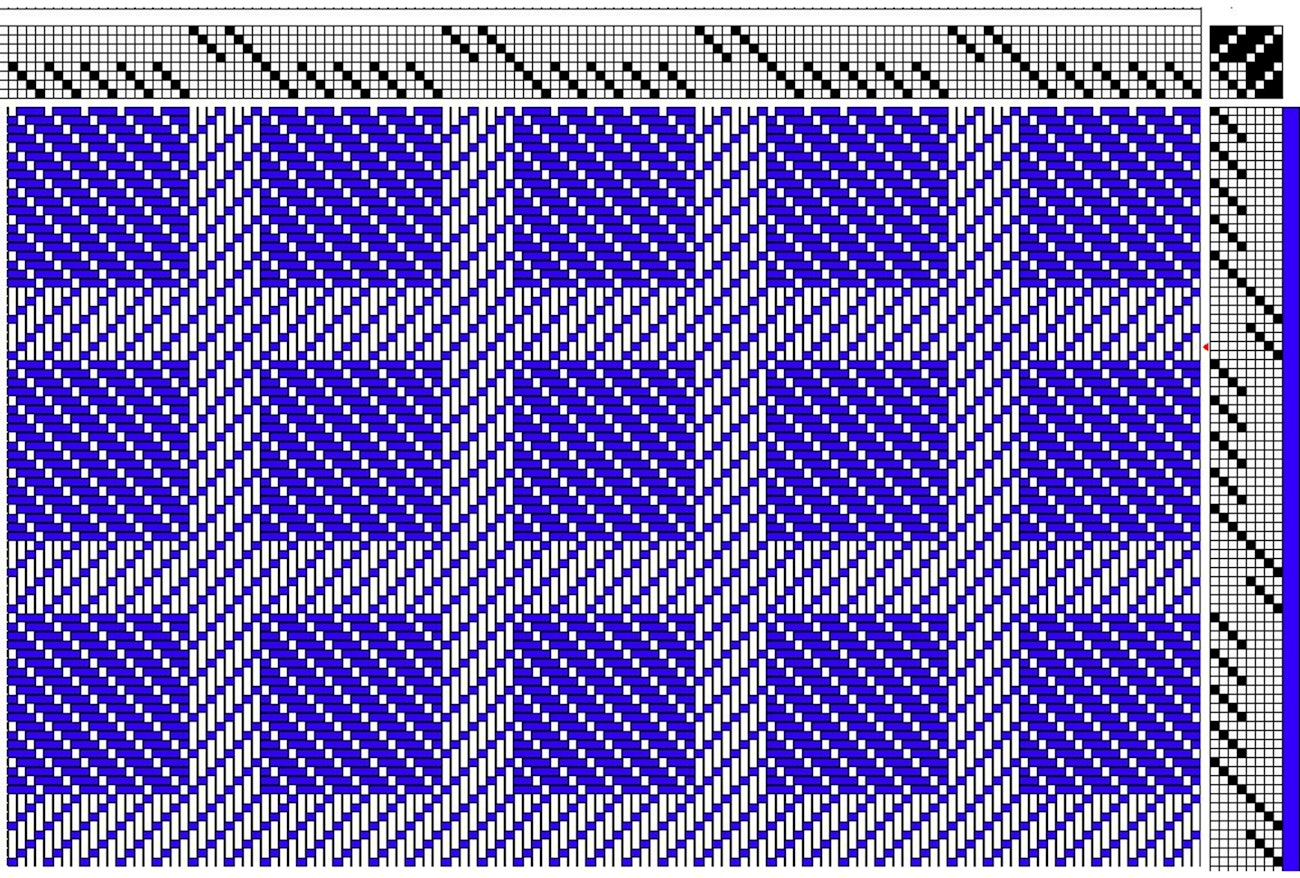

The warp-faced rep weave mats on the left were woven by Rosalie Nielson and featured in Handwoven Nov/Dec 2001. The weft-faced krokbragd mug rugs were woven by Anu Bhatia and are from Handwoven May/June 2022. Photo on left by Joe Coca; photo on right by Matt Graves.

While many weave structures are meant to be balanced weaves, some weave structures are meant to be very unbalanced. For instance, rep weave is warp-faced, meaning the warp shows exclusively in the cloth, while bound weave is weft-faced, and only the weft shows except in the fringe. If you are designing cloth that is very unbalanced, refer to similar projects in books and magazines to determine how to calculate for take-up, draw-in, shrinkage, and the like. And again, sampling is key.