Don’t miss this fascinating look at the plaid fabric that is a key part of Hawaiian workers’ clothing history. You can read the entire piece in the January/February 2020 issue of Handwoven. You’ll also find Linda Macdonald’s project, to weave your own palaka baby blanket.—Handwoven editors

I am a keiki o ka aina—born and raised in Hawaii, descended from immigrants brought to the islands to work on sugarcane plantations. As I became interested in weaving, I harked back to family memories of palaka, the Hawaiian term for a particular plaid fabric, usually blue and white.

Pre-European Hawaiians dressed in tapa (also known as kapa), a beaten cloth made from paper mulberry, but after European contact, they rapidly adopted harder-wearing woven cloth and dress. It is one garment in particular, a sailor’s shirt or “frock” as it was called, that was apparently transliterated as palaka, and the name shifted to mean the coarsely woven fabric from which the shirt was made. More recently, the term palaka became identified with the specific blue and white cotton twill plaid we know today.

Originally, palaka fabric was imported from England and America. Hawaiian and Portuguese workers adopted palaka shirts in the 1890s, and by 1922, palaka clothing was being produced for the plantation stores. The Japanese who came to the islands between 1885 and 1924 to work the fields brought their own clothing traditions to Hawaii; among them were skilled tailors who purchased palaka fabric and made the long-sleeved palaka jackets whose checked patterns were reminiscent of their own traditional checked goban-ji fabric. As a girl, I remember seeing Japanese workers going off to work in the cane fields dressed in denim pants and long-sleeved palaka tops, a necessary protection from the sharp-edged cane leaves. Palaka tops were similarly worn in the pineapple fields to protect workers from the sun and the spiky pineapple leaves.

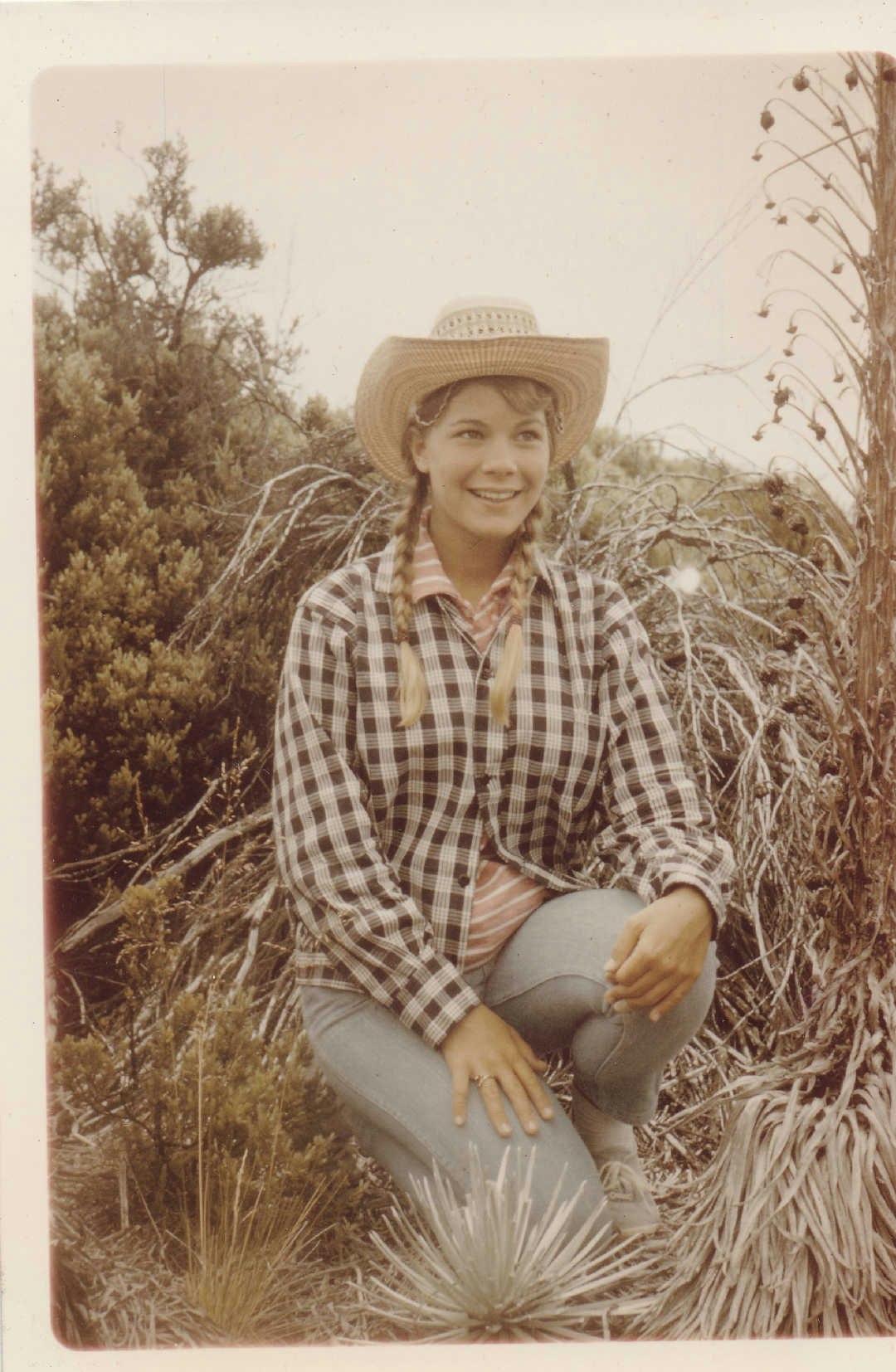

The author’s sister, Susie, wearing a palaka shirt in 1968. The shirt is similar to those worn by plantation workers and was probably purchased at Hilo Dry Goods. Photo by Cliff Davis

The tough twill fabric was also adopted by Hawaiian cowboys, who wore loose-fitting button-front shirts made of palaka. These in turn morphed into aloha shirts in the 1950s. Gradually, aloha print material replaced palaka as a fashion item, but palaka‘s appeal as a hardwearing, comfortable fabric was recognized by surfers, and palaka board shorts were the fashion statement for a while.

In “A Reflection on the Checker Past of Hawaiian Denim,” Taylor Hall concludes his research into palaka with the following: “It’s not a pattern made for money or excitement but to endure the hardships of work and appeal to the eyes of men and women burnt by the sun and hands stained by the earth.... It is unique because with all its initial differences in class, culture and race, palaka dressed every person...and told the rest of the world: I am Hawaii.”

Palaka fabric continues to be available in Hawaii, but it is a far cry from the tough cotton twill of days past. These days, it is a cotton/synthetic blend that is much lighter in weight. It’s also now available in a variety of colors, but the classic blue and white most appeals to me.

Linda Macdonald’s Palaka Baby Blanket project is just the thing for a new baby, wherever you live. Photo by Matt Graves

Linda Macdonald’s Palaka Baby Blanket project is just the thing for a new baby, wherever you live. Photo by Matt Graves

Palaka Baby Blanket Project at a Glance

STRUCTURE

Twill.

EQUIPMENT

4-shaft loom, 37" weaving width; 10-dent reed; 2 shuttles; 3 bobbins.

YARNS

Warp: 6/2 cotton (2,520 yd/lb; Valley Yarns; WEBS), Navy, 892 yd; Natural, 576 yd.

Weft: 6/2 cotton, Navy, 397 yd; Natural, 242 yd. 10/2 pearl cotton (4,200 yd/lb; Valley Yarns; WEBS), White or Natural, 50 yd. Note: Sewing thread or other fine cotton thread can be substituted for the 10/2 cotton.

Want to weave the Palaka Baby Blanket? You can find all the project details in the January/February 2020 issue of Handwoven.

Linda Macdonald was born and raised in Hawaii and has spent most of her adult life in New Zealand. Weaving became a sanity saver when her children were young, and today it helps keep the ravages of age at bay.