When I hired Joe Coca to shoot the first issue of Handwoven magazine in 1979, we were both ignorant novices. He was a kid lately out of photography school; I was a publisher making it up as I went along. That we kept working together for the next 40 years was more than inertia or complacency. It was that we kept learning.

You can look back through those old issues of Handwoven and watch it happening. In Joe’s case, more sophisticated lighting, more relaxed model shots, more eloquent fabric portraits developed. That was how we thought about the cloth shots. “Give it a Rembrandt look,” I’d say. And he would figure out how to do that. “Make this cloth look like it’s flying through the air!” I’d say. And he would cleverly lay it down on a big mirror on the ground, sky and clouds in the background.

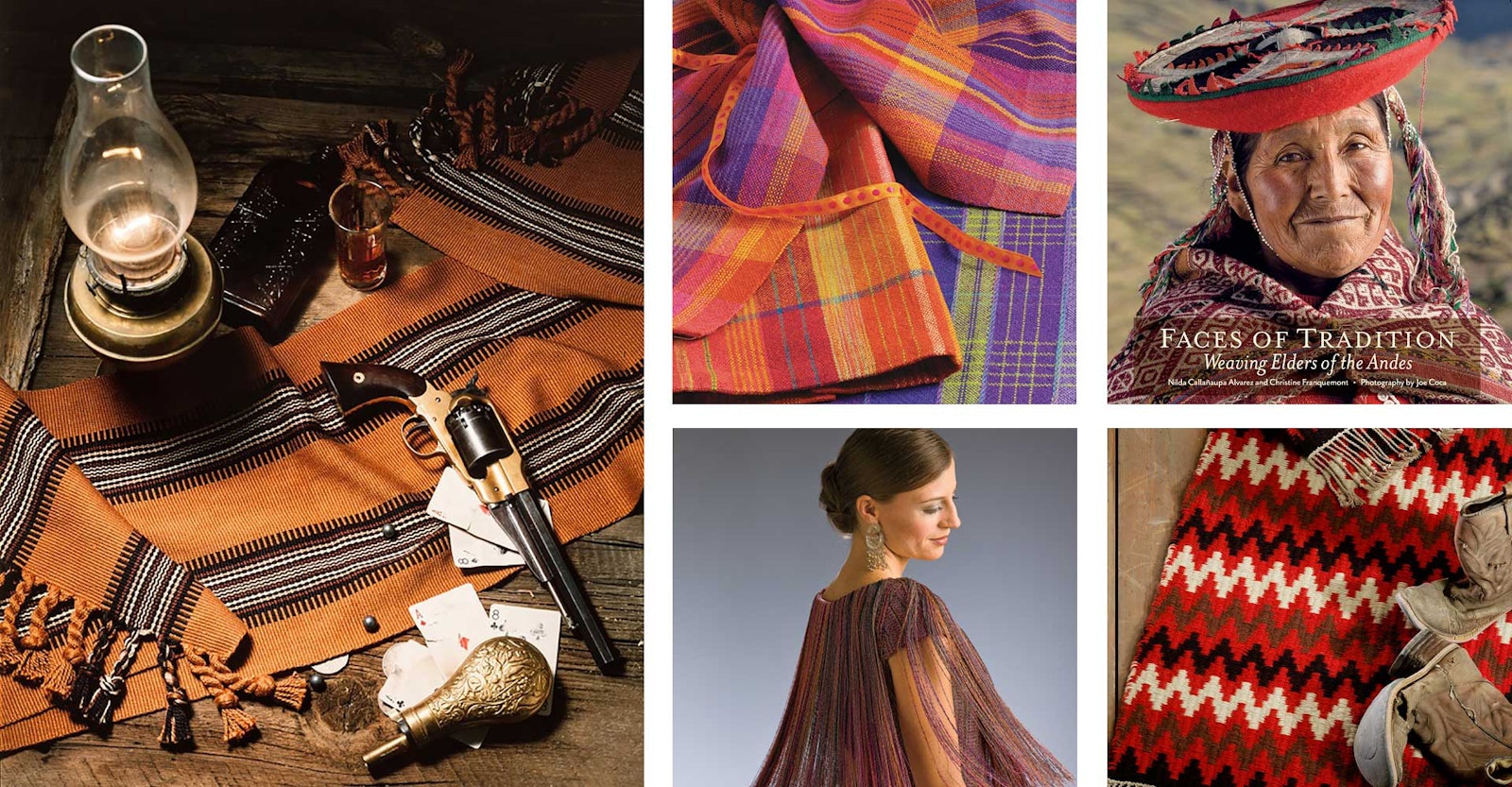

I think I demanded a do-over only once. I took a lovely brown runner to his studio (which was the same as his garage at that time), with a kerosene lamp for a prop. He added a pistol and a shot of whiskey. It made a good story, but “no weapons” became a house rule.

This photo of a runner with a pistol and a shot of whiskey inspired the “no weapons” rule for future Handwoven photo shoots.

Joe became a master of concealment. If you see a garment on a model whose arm is behind his or her back, it’s probably because the second sleeve of that garment didn’t get finished quite in time. If you see a beautiful woolen throw oddly folded down the middle, it’s probably because there was a honking big threading error right down the center of the warp (which we corrected in the instructions, of course).

And about those models: For years, we had no budget to speak of and used friends and relatives and strangers off the street. We once did a photo shoot in a local bar and persuaded one of the patrons to model a man’s handwoven shirt. He was about to fall off his chair, so he offered little resistance.

The Southwest Swing top from the first-ever Fashion issue of Handwoven (September/October 2011). For this issue, Joe worked to evoke the feeling of a high-fashion runway.

As years went by, other magazines happened along with new challenges. The Herb Companion was a real departure and meant figuring out how to shoot gardens and plants and food. Our food photography was very authentic—no tricks, sprays, or stabilizers—because we wanted to chow down as soon as the photography was done. On one occasion, we photographed (and consumed) an extensive medieval feast, only to have the film get washed down a storm drain before it was developed. That was before digital photography became the norm.

PieceWork magazine meant creating a look that would blend with historic photos without becoming corny. It also meant devising never-ending ways to photograph white lace, which our readers couldn’t get enough of. It meant celebrating diaphanous, see-through fabric instead of the solid surface textures of most handwovens.

During his tenure at Handwoven Joe photographed many towels and became an expert at making flat pieces of square cloth feel three-dimensional.

In the late 1990s, we started an offshoot of The Herb Companion, Herbs for Health. It launched a whole new direction in Joe’s career (and mine). I began a series on traditional healers in indigenous cultures. One trip to the Amazon basin and Joe was hooked on travel and the strangeness one encounters. It meant learning how to work with minimal equipment, to depend on available light in wretchedly dark environments, to work with people who had no common language.

To tease former Handwoven Editor Madelyn van der Hoogt, Joe Coca put a pair of dirty boots on a beautifully woven rug. The photo did not make it into the magazine.

Of course, textiles were involved. Most of the travel we did after that first trip was to chase down and memorialize artisans who were creating beautiful traditional textiles. That work became the basis of Thrums Books, my second career. We traveled to Peru, Guatemala, Mexico, Navajo Nation, Morocco, Laos, and China, learning that every part of the globe has its own distinctive palette, quality of light, and attitude toward cameras. It’s not the same as working in a studio where you have absolute control.

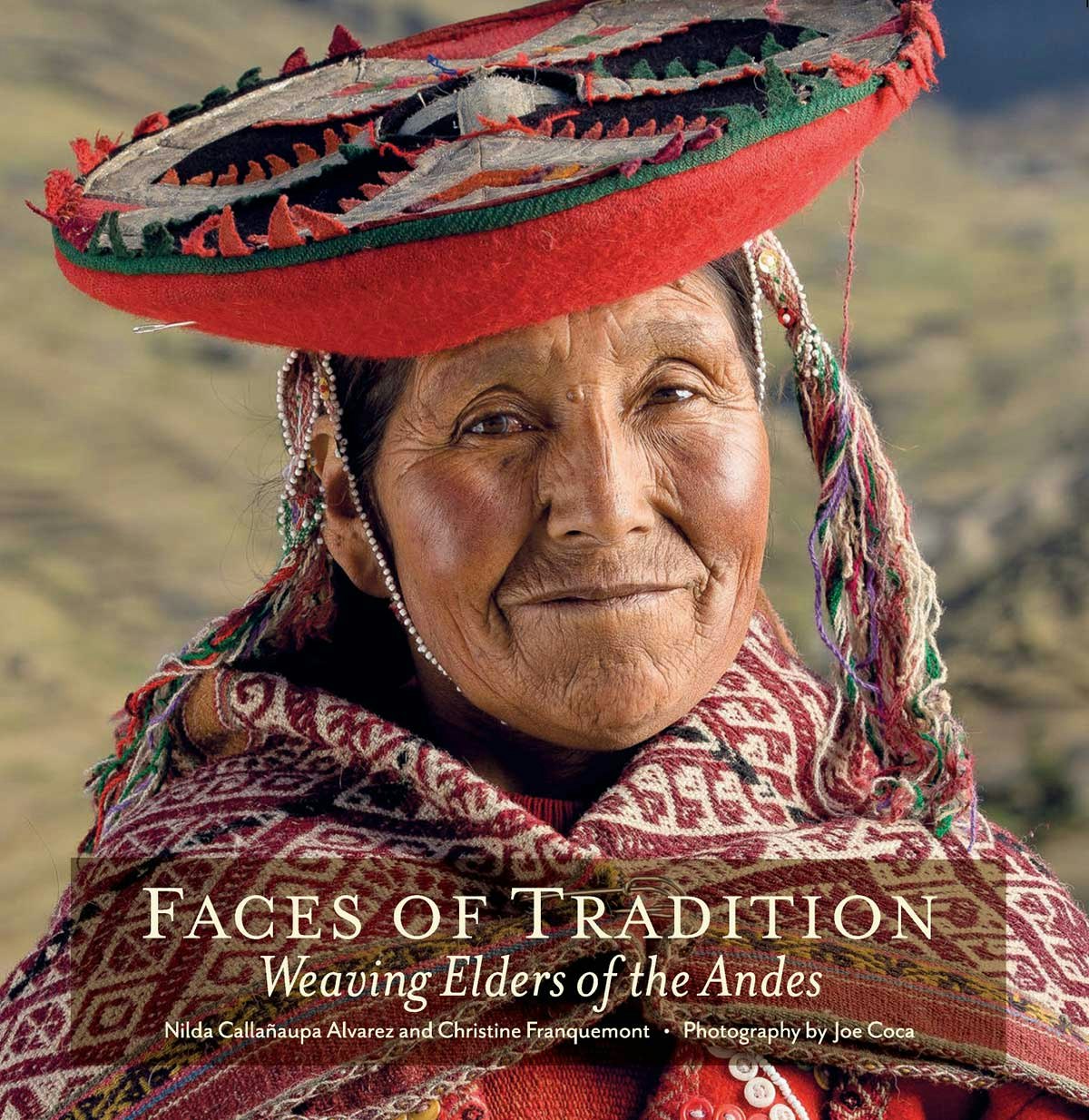

Somehow, Joe manages to have that kind of control and mastery wherever he goes, though. Ask him about his favorite photos from the travel years, and he’ll mention the cover shot from Faces of Tradition: Weaving Elders of the Andes. Not just because it’s a beautiful face and provides a deep human connection but also because this lovely Quechua weaver who was walking along the road had a needle in her hat. You can see it. It’s important to her. That level of attention to detail, when you have the entire Andes cordillera surrounding you, is one of the keys to Joe’s success: big picture, tiny picture, love of people, love of textiles.

The cover of Faces of Tradition from Thrums Books. Notice the sewing needle stuck in the left side of the woman’s hat. Photo Courtesy of Thrums

He’s had a lot to do with Handwoven’s success over the years. Thank you, Joe